The Maker of Spells

Sample Chapters

With illustrations from the Canadian special edition

Chapter 1

I stood alone in the mild sun at the prow of a river ship, bound north for sultry Aresia. The river was winding, and the landscape passed slowly. And as the ship meandered forward, my mind wandered back – to my last conversation with Artemis, nine days prior.

“You sent for me, Majesty?” The words sounded absurd – a parody of a subject addressing her queen. How long since I had called her Highness or Princess, even in public? Only a season or two? And yet the word Majesty felt like a sharp-edged rock in my mouth, awkward and painful.

“Thank you for coming, Spellwright” she said, permitting herself to sound tired. She motioned for me to join her at her desk. In spite of all that had passed – her parents assassinated, her court swirling with rumours of impending strife – her manner was calm. As if through a veil stirred by wind, I saw her familiar features: her rounded cheeks, softly curved nose and delicate chin, made firm by her purposeful expression; her mahogany skin glowing like heated wine in the wintry midday light; the depths of her liquid dark eyes, never more unfathomable than now. Only the queen seemed real, and the lover I had lost merely a dream, melting in the light of the waking world. Had I dared think that she would turn to me for comfort? Say my name with tenderness? Be my beloved Artemis once more? “Juno,” she said softly, and my gut flipped with momentary hope. “Juno, I’m so sorry for what I have to ask of you today.” A pit opened up inside me, and all the warmth in my body seemed to fall into it. Better never to hope than to hope and hear words like those.

Artemis picked up a scroll. “As I’m sure you know, the Aresian ambassador’s envoy returned last night.” Of course I knew. Amid all the rumours that the Aresian king was mustering an army, like his father two decades before, the envoy’s return had been anxiously awaited.

The queen tapped an index finger on the scroll. “He brought me a letter from King Amorgo’s own hand.” She leaned back wearily in her chair. “Proposing marriage.”

How long did I stare at her in the echoing silence?

Finally Artemis opened the scroll and read aloud. On behalf of the Realm of Aresia, I congratulate you on your coronation, even as I condole with you for the untimely passing of their most esteemed Majesties, King Eleos and Queen Olympia. I hope you will consider the benefit and prosperity that have accrued to both our realms in the twice-ten years of peace between them. However, I am keenly aware that Your Majesty has never visited Aresia. I beseech you to amend the omission by touring my realm in person at your earliest convenience. I fear I will grieve it as a slight if my court is not graced by your presence within the year. Artemis paused and looked up at me, then resumed. If I may add a personal entreaty to business of state, it is this: I ask for your hand in marriage. She set the scroll on her lap and gazed at me, unblinking. “You understand, don’t you? The ultimatum implied?”

I tried to open my mouth to speak, but it was already open, and there was no air in my lungs. I forced myself to breathe, and stammered “what will you do?” After an awkward moment, I added “Majesty?”

A rueful smile played at the corners of Artemis’s mouth, fitful, and then gone. She opened the scroll again and skimmed her eyes down it, selecting another passage. “Naturally you mourn your parents,” she read drily, “and out of respect for your grief I do not ask for an immediate answer. However, when your affectionate tears are dry, I implore you to fulfill my amorous hopes with all due speed.” She set the scroll down on the desk and waited for a comment. I sought words and found none. She spoke again, now with a metallic edge in her voice. “I count on you to advise me truthfully, Spellwright.”

“Majesty,” I said at last, “I can see no good option. If you accept his proposal, Demeterra becomes a vassal state of Aresia – like Posedi. If you refuse to visit his court…” I ran my mind over the letter, the situation, and what I knew of King Amorgo. “Given the reports that he’s been mustering troops… the business about benefit and prosperity and twice-ten years of peace… and the part about taking it as a slight if you don’t visit…” I inhaled slowly. “That sounds like a threat. If you don’t visit, Majesty, you risk war.” I pushed from my mind the images that rose there: my father, stone-silent before the hearth; the empty road where I had strained my eyes in vain for a cherished one who never returned. Please not another war. “And if you visit his court but refuse his proposal…” I struggled to express the fear that clutched at my throat. “I… am not certain you would be safe,” I said finally.

Artemis gave a bare puff of an exhale that I recognized as a grim laugh. “Safe,” she murmured. “No, I dare say.” She looked at me again. “What would advise, then?”

I shook my head. “I have no advice, except perhaps to stall for time, Majesty. King Amorgo says within the year, but he also says with all due speed when your tears are dry. Given his reputation for impatience…” I trailed off, my throat once again constricted.

“Mmmm,” said Artemis. “My thoughts exactly. It would take extraordinary diplomacy to hold him to a year.”

Extraordinary diplomacy. I understood her words all too well. The diplomacy that had saved the southern provinces from burning. My diplomacy.

“Ah,” I said.

Artemis looked down a moment to set the scroll carefully back in its place. “You are the last person I would have asked to broker a betrothal with King Amorgo,” she said quietly. “But there is no one else I trust. I need absolute loyalty, and…” she fished for words among the scrolls on her desk. “And tact, and… obstinacy.”

This time it was my turn to smile ruefully. Tact I had learned. Obstinacy I was born with.

She picked up a scroll marked with her insignia and paused before unfurling it – holding it motionless in her hand while she gazed at me, unblinking. She had looked at me exactly thus in the moments before she ended our betrothal. Only a handful of people knew Artemis well enough to understand that pause: a wordless farewell. She dropped her eyes, opened the scroll, and read aloud. “To Spellwright Juno Vera: I hereby appoint you Ambassador of the Realm of Demeterra to the Court of Aresia. I charge you with acknowledging King Amorgo’s proposal of marriage to your Queen, and affirming that he will receive an answer in one year’s time, on the nineteenth day after the winter solstice – neither later nor sooner than that day. I further charge you with learning what you can of King Amorgo’s wishes and reasons. Signed this Nineteenth Day after the Winter Solstice by Queen Artemis of Demeterra.” She tipped a candle over the scroll and sealed it, then picked up a second scroll, larger but on rougher papyr and without any formal decoration. “This details the current diplomatic matters you will need to handle. Mostly routine business. There’s a roadworks proposal that the north-eastern provinces are anxious to see realized. But the matters of greatest interest are those not listed.” She dropped her voice to a murmur. “Find out what you can about the rumours – the army, the spies, my parents’ assassination, all of it. Find out how much is true. And Juno…” she looked me in the eye as she handed me the pair of scrolls, and for a moment she was my own Artemis again. “Try to find me a third option. I can’t stand the thought...” A sickened expression flashed across her features, but she clamped her mouth closed and broke my gaze, straightening her back and becoming the queen once more.

My mind finished the sentence for her. “Can’t stand the thought of marrying him.” The woman who had broken my heart now needed me for this? How terrible, that in the face of such coercion she had only a spurned betrothed to turn to. But the lost lover had vanished into the monarch, and there was no one to tell that I understood her desperation.

I stood up and bowed. “Of course, Majesty.”

Chapter 2

Thwap. I was wrenched out of my reverie by the snapping sound of wet linen shaken out, unnervingly close to my face. I heard a giggle, but when I turned to look, my attendant Justine stood nearby, nonchalantly hanging a freshly washed tunic to dry on the railing of the ship’s upper deck. I set out to frown and found myself smiling. Incorrigible girl, I thought, and then thank the stars she’s coming with me.

I reined in my smile. “Mind you get that…” I paused and thought better of it, and fell silent.

“Mind I get what, Ambassador?” Justine asked in a tone of supreme innocence. She was an exuberant girl of twenty-two, and had now attended me for the better part of a year. I had chosen her for her high spirits, hoping her presence in the evenings would lighten the gravity of court life. Mostly it was my own gravity she lightened.

I sighed. “I was going to say mind you get that tunic down from the railing before we arrive.” Justine rolled her eyes theatrically, and I smiled again, knowing that she would lose no opportunity to tease me for my pedantry.

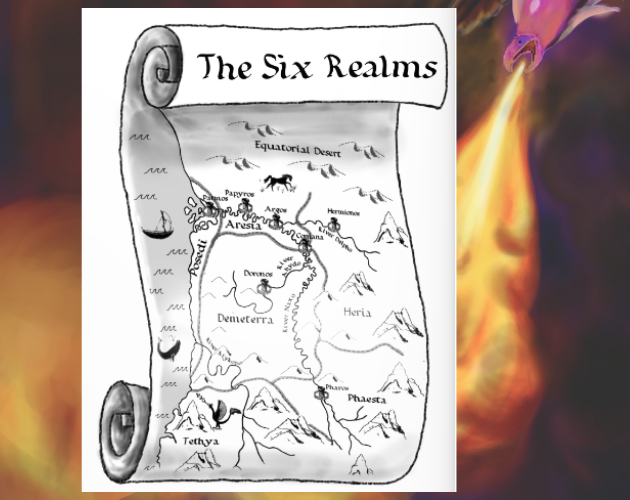

I gazed at the landscape as it drifted by. To the east, fields of grain alternated with dairy pastures, stretching seven days’ hard ride toward the border with Posedi. To the west, the terrain rolled upwards to the ridge of foothills marking the border with Heraia, blue-green with mist in the far distance. These were sights I had seen only in tapestries, for I was already further north than I had every been before – an absurd predicament for an ambassador. I closed my eyes and forced my memory back to the last time I had arrived in a foreign court on an impossible mission.

“Majesty,” I remembered hearing the attendant say, “there is an… ah… emissary here from Demeterra.” I had been standing in the corridor of an unfamiliar castle, in Pharos, the capital of neighbouring Phaesta. I was grimy and exhausted from many days’ ride. And I had one chance to save my country.

“What do you mean, an emissary?” came a deep, gravelly reply. “An envoy? Where is Ambassador Phillip?”

“Here, Majesty,” said the Demeterran ambassador, sweeping past me through the vaulted doorway. “Not an envoy, Majesty – a spellwright, here on business with Prince Morpheus. I knew nothing of her coming until just now, when she arrived.”

Voices rumbled, and the attendant emerged to beckon me through the doorway, into the private study where King Chrysus sat with his brother. Maps and papers sprawled across the oaken desk, and a modest noonday meal had gone cold on the sideboard. When I entered, the two men stared at me in tense silence. With their raven-black braids, black eyes, and deep brown complexions, the king and the prince looked at me as if a goose had waddled in and demanded an audience. Pale hair, pale eyes, pale face: I looked the part of a servant or farmer, astonishingly dressed in soiled spellwright’s robes.

In Phaesta, I knew, commoners were forbidden from attempting spells, let alone becoming sorcerers. And given the spells the Phaestan sorcerers practiced, little wonder they guarded their magic so jealously. Spells to hold rocks – nay, whole mountainsides – in precarious arches while miners toiled beneath. Cleansing spells that dissolved human filth, allowing the poorer districts to be more densely built than Demeterran law would ever have permitted. Forfences of animals and even, in some circumstances, people: magistrates could order peace bond spells to keep quarrelling parties at a distance. The aristocratic sorcerers of Phaesta took seriously their duty to regulate the use of such powerful magics – and none more so than stern Morpheus, crown prince and Chief Sorcerer of the realm, and the middle sibling of the king.

There was no point in apologizing, either for my appearance or the interruption. I bowed. “I am here on behalf of King Eleos,” I said. “I have matters of import to discuss with Prince Morpheus.”

Eyes bored into me, seemingly from all angles.

Morpheus spoke, his voice like the somber boom of a bass drum. “And you are…?”

I bowed again, and held my face rigid to avoid cringing. “Spellwright Juno Vera.” It was a villager’s name, chosen by my commoner father, Julian Vera. My mother had a very different name. Her family, though poor, claimed distant nobility, and her name, Iris Kyano, marked her as a descendent of the Eleniqi, the bringers of light – the ancient heroes who had crossed the equatorial desert from the north and brought the arts to the Six Realms. But neither my mother’s name nor her lineage was of any help to me now.

King Chrysus turned an irate glance to Ambassador Phillip. “And you’re sure her business here is legitimate, Ambassador?”

“Yes, Majesty,” Phillip said. “The scroll she brought from King Eleos is sealed with his personal stamp.” He bowed and handed the scroll to the king, who broke the seal and read aloud in a gruff staccato. “To King Chrysus of Phaesta: In these times of unprecedented crisis, I have charged Spellwright Juno Vera with requesting help from your brother Prince Morpheus, on behalf of the Realm of Demeterra. Her proposal may have merit, and may benefit both our realms. Please provide her hospitable welcome in Pharos. Signed this Twenty-Third Day before the Spring Equinox by King Eleos of Demeterra.” Chrysus tossed the scroll aside impatiently. “Hardly a ringing endorsement,” he said, “and no details at all of what this proposal entails.” He gestured toward me, still addressing Phillip. “And you know this… individual?”

“Mmm,” said Phillip, and paused. I again restrained a cringe. Phillip was the queen’s brother: Artemis’s uncle. But our betrothal was not yet public. Did he know? And would he say? “I know her to be an assistant spellwright, Majesty,” he said. “A capable healer, I believe, and something of a favourite of the Princess.” At this, Chrysus and Morpheus looked at each other with inscrutable expressions. “I believe,” Phillip went on, “that Chief Spellwright Melissus holds her in fairly high regard.”

“Then why,” said Morpheus, “did Melissus not come himself, or send an envoy with a message of substance?”

I interrupted. “Because I am here in defiance of Chief Spellwright Melissus.” All eyes once again turned to me. “I broke protocol and requested an audience with King Eleos, who granted me his leave to come here. Prince Morpheus, I insist that you hear me out.” The king scoffed and the prince raised his eyebrows in affronted silence. Probably no commoner had ever insisted on anything to him. I squared my shoulders and looked surly Prince Morpheus in the eye. “I am here about the dragons.”

Had this scene unfolded less than a year ago? It felt like longer. The southern foothills of Demeterra had been devastated. The seasons and elements were out of balance, the wild game of the high mountains strayed into the foothills, and the dragons, lured by their accustomed prey into Demeterra’s lush farmland, preyed on anything and anyone. Chief Spellwright Melissus had ordered a redoubling of all the customary evenspells to restore balance, but they were insufficient. Baffled, Melissus ordered the recitation of forfencing spells to banish the dragons, although such coercive magic had never been the Demeterran way. Most of us had never forfended a mouse, much less a dragon. Convinced that this was wrong-headed, I went directly to King Eleos.

On bended knee, I pleaded that he hear me out, and in the face of the whole court’s ridicule, I made my case. Demeterra is not alone in devastation. Phaesta, where forfences are routine, has also suffered dragon attacks, and if their sorcerers cannot banish the fiery predators, the spellwrights of Demeterra stand no chance. The only remedy is to rebalance the seasons, and given the scale of the distemper, our incantations will never work without the participation of the dark sorcerers of Phaesta. It was a mad proposal, but the king had little to lose.

The journey from the Demeterran capital of Doronos to the Phaestan court in Pharos had only increased my conviction, for every traveller I met told a different story to chill the heart: miners torn to pieces by the dozen, townspeople burned to the bone as they fled through charred streets, and whole districts shut down as fear spread from town to town. Knowing this, I knew that Prince Morpheus, beneath his impassive demeanor, must be as desperate as Melissus. And so I spoke to him as to a brother: direct, certain, and as obstinate as himself.

Turning this memory over in my mind, I took heart. It had been the making of me. Morpheus agreed to order every sorcerer in Phaesta to learn and recite Demeterran evenspells, and it worked. The dragons returned to their mountains. I returned home a hero. Grey-haired Melissus, disheartened at his failure and feeling the pull of his grandchildren in the countryside, retired from his post, and I was appointed Chief Spellwright of Demeterra. King Eleos and Queen Olympia at last granted their blessing, and Artemis and I announced our betrothal. The promise of many years together stretched in front of us like so many fields of blue-flowered flax, away into the distance and beyond the curve of the world.

And yet here I was. I let my head fall onto my arms where they rested on the ship’s rail. Even if I succeeded in finding Artemis an alternative, she would surely remain lost to me. And what hope did I have of success? Haughty Prince Morpheus had set aside his prejudice because death, pain and poverty loomed over his country. But King Amorgo? Ruler of the most prosperous of the Six Realms, reputed to command the mightiest army in the world, Amorgo of Aresia wanted for nothing. What reason would he have to listen to me – or to anyone?

Chapter 3

By the time we crossed the border into Aresia two days later, the river Naxo was wide and slow. The border was marked by the island of Comana: the last rocky outcropping of the receding foothills, and the last fortified outpost of Demeterra. The siege of Comana had been the turning point in the war. The archers that manned the fortress had stood their ground and safeguarded the upper Naxo, but the siege went on and on. Squadron after squadron of Demeterran infantry strove to beat back the Aresians and lift the siege. And wave after wave of Aresians came from the northwest to reinforce the besiegers. When King Typhon finally withdrew the remnants of his forces, the hungry and illness-wracked Demeterrans within the fortress had lowered their drawbridge and stepped out into a scene of unfathomable carnage – of desperate and injured comrades struggling to bury the rotting, stinking dead. My father had been among the archers trapped within Comana. And my childhood sweetheart had been among the dead on the riverbank.

I stared at the fortress as the ship floated past, fixing my eyes on it – anything to avoid looking at the shore. Past Comana, the Naxo veered west and began its snaking journey toward the sea over a wide, flat plain. The autumn floods had receded, and the year’s crops were already half-way to harvest in the year-round heat. The navigable channel of the river meandered through rice paddies and perch farms, and although the dry shore was distant, I caught glimpses of vivid green fields dotted with date palms, where the ship’s crew told me cotton and farro were grown.

Artemis had sent me to Aresia with the customary retinue of an ambassador: an attendant and an envoy. Marc, the envoy, would meet us in the Aresian capital of Argos. He traveled on horseback for the sake of speed. A direct overland route and many changes of horse meant he could cover the distance in only six days, while the river ship took twelve. He would ride back and forth to Doronos throughout my stay, ensuring that communication between myself and the queen was not intercepted. Justine, of course, travelled with me. She was a city girl – a wheelwright’s daughter – and eager to see the sights as the ship glided by. Seeing her excited expression at each new shift in the landscape, I smiled, remembering the cheekiest prank she had ever attempted: dressing in my spare set of robes and fooling Artemis into addressing her as sweet woodlark. I had teased my beloved for that – “do all pale-haired women look the same to you, dearest?” The princess had stood a moment torn between hilarity and annoyance, while her own attendant stood by looking scandalized. “She could pass for your younger sister, Juno, dressed like that.” “So your answer is yes, we all look the same?” I had wrapped my arms around her and kissed her ear, prompting Justine to roll her eyes and vanish into the servants’ quarters. The ease of my former banter with Artemis seemed strange to me now, like a familiar melody played in the wrong key.

And then, at midmorning the following day, there it was – the walled metropolis of Argos, standing at the fork of two rivers. The swift Delpho, running down from mountainous Heraia, flowed into the mighty Naxo, moating the city on every side but the east. The union of the waters widened the Naxo till it seemed like a serpentine sea, its vast floodplain extending past the horizon on either side, and stretching westward toward the distant sea. The stone ramparts, blue domes and golden spires of Argos rose out of the green floodplain and shimmered in the blazing sun. For a moment the inner chatter of my misgivings ceased, and I stared at the city in wonder as the ship drew near.

Marc was waiting for us on the pier with a small group of Aresians. He had served four years under my predecessor, and although he was about my age, his face was roughened, his hair bleached white-blond by the sun. Like my father, I thought – or at least like the father I remembered from my childhood. He and two attendants stepped aboard, and while the attendants helped Justine with the luggage, Marc approached me with a friendly bow and motioned to two men still standing on the pier. “Your welcoming party, Ambassador. The man on the left is Lord Peisander, the king’s Master of Ceremonies.” I glanced discreetly at the pier, noting Peisander’s portly figure and aristocratic bearing. But my eye was drawn to the second man, and my brow jittered upward in surprise before I could stop it. Though tanned, he was pale by birth, his hair the colour of ripe wheat. A commoner like me. But his servant’s tunic was embroidered like a lord’s ceremonial cloak. Taller than Peisander and slender as a birch tree, he cut a striking figure. Marc saw my surprise. “The other is Larance Alta,” he said, “the Steward of the King’s Household. Don’t let his name or title fool you. Commoner or no, he holds great authority, and has the king’s ear.” Marc smiled. “Much like you, ambassador.” So I would not be the first of my kind in Argos. I didn’t know whether to be relieved or unnerved.

I stepped toward the gangway, and Marc fell in behind me. As I disembarked, Peisander bowed in formal greeting. “Ambassador,” he said, “it is my honour to be the first to bid you… welcome to Aresia.” He made a sweeping gesture at nothing in particular. “His Majesty King Amorgo sends his warmest welcome and expresses his utmost happy anticipation of conversing with your esteemed self at the earliest opportunity.” Out of the corner of my eye, I saw Justine bite back a snicker at Peisander’s sickly-sweet language. I studiously refrained from smiling until I could do so blandly.

“Thank you, Lord Peisander,” I said, cooking a few degrees of warmth into my voice and expression. “I look forward to meeting King Amorgo.”

Peisander remained momentarily in a listening posture, as though waiting for me to say more. Realizing I would not, he set himself back into motion – nodding, gesturing, leaning forward in a half-bow. “I like your style, Ambassador,” he said. “Getting right to the point. Very forthright. Very good. Well then, let us, ah, allow me to also get right to the point. Shall we? If you would like to proceed, I shall be glad to do so. I entreat you to step this way, Ambassador.” He gestured to a waiting chariot.

“Thank you,” I said again, groaning inwardly. A mere thank-you passed as forthrightness here? And we had to ride a chariot? I had ridden a chariot only once before, in a celebratory procession after my return from Pharos. High-ranking nobles, accustomed to chariots since childhood, thought nothing of the skill and attention required merely to remain standing while in motion. But to also control the horses, converse with one’s companion, wave to admiring crowds, and manage to look impressive? Thank the stars I don’t know the city, I thought, and can’t be expected to drive. Peisander stepped into the chariot and stood on my left. To my surprise, Steward Alta stepped up after him, moved between us, and – further surprise – picked up the reins.

“If I may say, Ambassador…” said the steward, politely waiting until I turned toward him. His hands, holding the reins, were as pristine as any courtier’s. He spoke quietly, pitching his voice to reach only me in the tight quarters of the chariot. “His Majesty has repeatedly told me to spare no pains in helping you feel at home.” He turned his eyes from the horses to smile at me, somehow deferential and intimate at once. “You can ask for anything, and I will personally see to it.” A hint of mischief scampered across his grey-green eyes like a mountain vole and was hastily suppressed – or seemed to be. He turned back to the horses and shook the reins, cuing them into motion with practiced ease.

“That’s very kind of you, Steward Alta,” I said, keeping my tone blandly polite. I recalled Marc’s words. He holds great authority, and has the king’s ear. I could hardly be too careful.

Chapter 4

My quarters in the castle consisted of a bedroom, a sitting room, and a small study, as well as an adjacent room for Justine. Food was brought to us in the sitting room so that I could have a quiet noon meal before my formal audience with the king. The steward appeared in the doorway alongside his staff, to personally oversee the service, as he put it. Justine, having speedily unpacked most of our things, was already feeling at home in the new space. She offered me my cup of tea with an extravagant bow. “Would your esteemed self like lemon with that?” she asked, smirking gleefully.

I looked at her sternly. “Yes, thank you Justine,” I said neutrally, postponing glancing at the steward as long as possible, though I was certain he had caught the mockery of Peisander. But when I did turn my head, I found that he was grinning at Justine, his eyes crinkled and his shoulders shaking in silent laughter. No help for it now.

“I see you share Justine’s appreciation for the finer points of courtly language, Steward Alta,” I said, allowing my mouth to twist into a smile with only a transparent veneer of restraint.

He laughed aloud and turned his smile to me, exuding shy warmth and boyish mischief. “Ambassador, you have no idea.” Finding myself mirroring his expression, I raised my teacup to hide it, and sipped slowly. He holds great authority. Tread carefully. I sat down to eat and thanked him for the attentive service. He took the hint and bowed himself out.

The audience with King Amorgo began, of course, with formalities – and the whole court in attendance. I knelt on one knee and delivered a speech that to me seemed extremely formal. “Majesty, I am honoured to speak on behalf of Queen Artemis of Demeterra. As her ambassador, I am at your service to act as a liaison between yourself and my country. I am pleased to report that my queen has agreed to consider your proposal of marriage and will provide an answer in one year’s time, on the nineteenth day after the winter solstice, neither later nor sooner than that date.” I bowed my head and held out my official appointment scroll.

Amorgo raised one impeccably shaped eyebrow and waited. Then raised the other eyebrow. After a baffled pause, I raised my head and looked at him – he seemed expectant. “Would your Majesty request me to read it aloud?” The king gestured to Lord Peisander to accept the scroll and read it aloud, which, after some throat-clearing and preamble, he did. Amorgo nodded thoughtfully as Peisander returned the scroll to me, then smiled.

“You are to learn of my wishes and reasons?” The king laughed. “That’s no trouble. I’m happy to discuss them.” He waved a casual dismissal to the rest of the court, and, as they filed out, invited me to sit on a chair to his right. Up close, he had an eerie beauty. His crown sat on a head shaved to the smoothness of sea-polished basalt. His smile was chalk-white, his beard immaculate. “Of course you already know my reasons, since I enumerated them in my letter,” he said. “I thought for the most part they are self-explanatory.” He looked at me, his expression bland and friendly, yet with an intensity in his eyes that told me he would scrutinize my every word and movement.

I nodded deferentially. “Firm alliance and the mutual prosperity of both realms, yes,” I said.

The king knit his perfect brows quizzically. “And my personal regard for your queen? Do you not consider that self-explanatory?”

I froze. Personal regard? I remembered Artemis skimming the letter, choosing the important passages to read aloud to me. Frustrated to find myself caught unawares, I wished I had asked to see the full scroll. I smiled as if the king had said something witty. “Of course I find high regard for her self-explanatory, Majesty,” I said. “But Queen Artemis expressed more interest in the diplomatic side of the question.”

“Did she,” said the king with a frosty smile. “And it was in the name of diplomacy that she broke your betrothal and sent you here?”

I paused, struck with the thought that he, too, had been caught unawares. “Not exactly, Majesty,” I said. “Our betrothal had already been broken off for some days when your letter arrived.” I watched Amorgo for a response. His features were motionless.

After an unsettling pause, he spoke. “So she did not confide in you her reaction to my profession of love?”

Profession of love? Good stars. “No, Majesty,” I said blandly, while my mind raced. What in the cosmos had been in that scroll? Artemis had never been to Argos – just as Amorgo had complained in his letter. She had skipped Aresia on her Grand Tour, on account of the resentment still harboured by the Demeterran populace even years after the war. Had Amorgo ever met her?

“Did she ever speak of me?” he asked. “You were betrothed the better part of a year, were you not? She must have told you a great deal.”

“She did,” I said, recognizing the jealousy he hoped to provoke. I found a dark closet for it at the back of my mind and slammed the door closed. “That is, she did tell me a great deal. She did not mention having met you, I’m sorry to say. Was it recent?”

Amorgo smirked. “We first met nearly twenty years ago,” he said. “At the signing of the peace accord, and the festival afterward. We were both little more than children, but she made quite an impression. When I visited Doronos on my Grand Tour, we spent many happy days together.” His Grand Tour. Of course. It would have been only a few seasons before hers, in the days before I paid much attention to such things. Jealousy threatened to burst once more into my thoughts. How could she not have told me? The king’s eyes blazed, even while his features remained friendly. “Had I not been called home prematurely by my father’s illness,” he continued, “I would have sought her hand at that time. Her beauty and grace were unparalleled.” He smiled a devilish smile. “I assume you agree?”

I could see he was enjoying the sport of baiting me, so I summoned the stubborn devil in me that likewise relished the game. Artemis herself suspects him in her parents’ assassination, I reminded myself. “Although she is very beautiful and very graceful,” I said, “I would call those the least of her qualities.”

“Oh? And what are the greatest?”

“Wisdom, kindness, devotion to her country, and…” I paused to let tension build a moment. “Affection for her family. She was deeply attached to her late parents.” I watched Amorgo closely to see if his reaction would reveal anything. It did not. He only nodded with maddeningly appropriate sympathy.

“It is unfortunate that a person’s best qualities are so often a cause of suffering,” he mused. “This must be a difficult time for her. I well remember the pain of gaining a crown at the expense of losing a parent. However little leisure I had for courting, in those days, it was a great blow to me that she omitted Aresia from her Tour.” Now it was his turn to pause for effect. “My hope is that you’ll help me in persuading Her Majesty to visit Aresia before the year is up. I would like an opportunity to woo my bride in person.” I pulled my mouth into a thin smile. “Aresia is particularly beautiful in the spring,” he continued. “Perhaps she can be induced to join us here for the equinox.”

“I am happy to relay whatever invitation Your Majesty wishes to extend,” I said, carefully avoiding even a whisper of commitment.

Amorgo permitted himself an exasperated sigh. “Your esteemed self has already made a name here as a plain speaker, so let’s do away with the finer points of courtly language, shall we?”

I barely contained an offended gasp. Friendly Steward Alta had repeated my words verbatim to the king, in the short time between that conversation and this one? He has the king’s ear. Indeed. He was the king’s ears.

Amorgo continued. “Artemis would not have chosen you, of all people, as her ambassador without good reason.”

I inclined my head to acknowledge the compliment, ignoring its backhandedness. “I hope I have earned her trust and will contin…” I had chosen the platitude for its spongy softness, but it shattered against the king’s interjection like glass against stone.

“Tell me, Juno Vera,” he said, ejecting my name from his lips with a force that emphasized its plainness, “who are you, and how did you come to be first the betrothed and then the ambassador of Artemis of Demeterra?”

“I’m the daughter of an infantryman and an impoverished noblewoman,” I said, refusing to be embarrassed. “I was apprenticed to my aunt, a provincial spellwright. My local reputation earned me an assistant position in Doronos, where I served King Eleos for over ten years.”

“Serving and advancing are two different things. A year ago, no one had heard of you. Then one day my ambassador sent word of the princess being engaged to a Chief Spellwright with a commoner’s name. How?”

I ran mental fingers over an array of words, selecting the ones that felt firmest. “I undertook a collaboration with Prince Morpheus of Phaesta that proved beneficial to both countries,” I said at last.

“So Eleos rewarded you with rank, fortune, and his daughter’s hand?”

I kept my face impassive as I registered the implications of Amorgo’s question. Artemis and I had kept our betrothal secret from all but immediate family until after my promotion, and she had broken it off days after her parents’ assassination. Did Amorgo, with his honeyed words and his threatening army, truly think that my princess had been betrothed to me against her will? A seething hotspring of rage and disgust welled up in me, but the stubborn demon inside kept me silent. If there were a chance Amorgo really believed me capable of claiming a woman’s unwilling hand for the sake of advancement, then it was to my advantage to let him keep thinking it.

“King Eleos’s favour meant a great deal to me,” I said, smiling. “And Queen Artemis’s trust likewise means a great deal.”

“It’s a step down, isn’t it?” Amorgo asked slyly. “From Chief Spellwright to Ambassador?”

“But Ambassador to Aresia?” I said, declining to note anything in the question except an opportunity to flatter. “Surely not, Majesty.”

“What is King Amorgo like?” Justine demanded when I got back to my quarters.

“Oh, tall, dark and handsome, of course,” I said – truthfully. “And charming, and graceful, and the devil himself.”

Justine dropped the garment she was mending and came eagerly to hear more. “What did he do?”

“He claimed to have real feelings for the Queen.” I said. “Apparently he had courted her years ago. He pressed an invitation for her to visit Argos in person. And he parroted back to me our own words about esteemed self and the finer points of courtly language.”

Justine gasped, half in horror, and half in glee. “Was he angry?”

“On the contrary,” I said, truthfully again. “I think he was pleased to make that little joke” – this made Justine beam – “and even more pleased that it rattled me.” Her face fell. “Please be careful what you say, and in front of whom,” I said. She nodded in puppyish apology. “Now your turn,” I said. “What have you learned about Aresia in the attendants’ hall?”

“Oh, barrels’ worth,” Justine answered. “Even the lowest paid attendant makes thirty drachmae a year in addition to room and board.” I raised an eyebrow. My own salary as an assistant spellwright – a position usually held by minor nobles – had been only forty-two drachmae. “I’m to have my meals in the attendants’ hall, and we get coffee every day at morning and noon.”

I broke into a snorting giggle, feeling a bit of tension dissipate from my gut. This explained some things. “How many cups of coffee have you had today?”

“Three. Why?”

“Oh, you’re not going to sleep tonight! Stick to one cup at breakfast.” She looked miffed. “That’s advice, not an order,” I said gently, squeezing her shoulder. “And let’s keep it that way.” I gave her a mischievous smile. “If you guzzle coffee till you’ve tuned yourself up like a shrill harp, and then make poor decisions that jeopardize our mission, it will become an order.”

“But I can keep the kitten?”

“I… what? What kitten?”

“The Heraian ambassador’s cat has kittens that are old enough to leave their mama, and she gave me one.” Justine reached into a basket and pulled out a tiny grey kitten, its eyes still blue and wide and trusting. “I think she felt sorry for me, because I stopped to pet the kittens, and then her envoy Stellan cornered me and told me a long boring story about his brother’s olive harvest, so I was stuck there, so then the ambassador said I could take a kitten. She said to give it to you with her compliments.” Justine looked at me imploringly.

“Yes, you can keep it, and yes, it can be yours,” I said.

Chapter 5

In spite of my warnings to Justine, I was the one struggling to sleep that night. I lay awake, turning over Amorgo’s words in my mind. I will grieve it as a slight if my court is not graced by your presence within the year. Had this truly been an ultimatum? Or only a jest from a long-ago suitor? Rank, fortune, and his daughter’s hand. While technically true, the phrase hinted at a grotesque version of events, so achingly far from the truth. And yet the truth had begun to feel hazy. I closed my eyes and cast my mind back to my first encounter with Artemis, determined to wear the memory smooth rather than risk letting it fade.

When I first met her, I had already worked at the Demeterran court nearly seven years. When I was hired, the princess was a shy girl of nineteen, and as the years cycled on, I had failed to notice her grow up. I was surprised one day to hear that she had departed on her Grand Tour, and even more surprised, upon her return a year later, that her parents made her their lead advisor on matters of international commerce. Could that timid thing really be ready for such responsibility? However, since no calamities of failed statecraft ensued, and my own work did not overlap with hers, I soon thought of other things, and forgot about the princess almost entirely.

That is, until I found myself in her quarters.

She had injured her hand during her morning archery practice. Archery practice? The princess? I thought. Surely that sweet plump child can’t draw a Demeterran longbow? Yes, her attendant assured me, she had practiced archery since childhood, but today her bowstring had snapped and cut her hand.

For the royal family, it was customary for Chief Sorcerer Melissus to perform the halmaking, or healing spell, himself. But Melissus was in the countryside visiting his grandchildren, and had named me as his stand-in – the first time I had held such an honour. Would I be so kind as to attend to Her Highness? Eager for the rare opportunity to have my work noticed by the royal family, I gathered up my materials and hurried to her quarters.

As soon as I walked in, I realized how badly I had misjudged the princess. She sat in a posture of easy alertness while her attendant cleaned the injury. Her mouth barely registered a grimace as the attendant applied an astringent that routinely made officers of the guard hiss through gritted teeth. Although she was of medium height at most, and perhaps even plumper than she had been in her teens, she moved purposefully, every inch of her self-possessed. Regal. The rowanwood longbow that leaned unstrung in the corner was taller than her by half, and heavy – a war bow, capable of piercing armour. Beside it lay a sheaf of oaken battle arrows with standard-issue goose fletching. I had watched my father try to teach the farmers of our village the longbow, and many a stout ploughman had sweated and gasped with the strain of drawing it.

The occasion demanded that I bow, but I found myself bowing in sincere and astonished admiration. As soon as the attendant was done, the princess waved for me to come and sit next to her. Her motion was collected, with no excess or theatre. I unrolled my packet of materials, lit a candle, and got to work. I laid out the talismans in a circle around the candle – the translucent moulted skin of a coin-sized crab, the shell of a hatched hummingbird egg, a sprig of mountain heather, an acorn, and a dried jasmine blossom.

The princess stopped me. “What’s that for?” she asked, pointing to the heather. “Melissus doesn’t use that.”

“Mountain heather confers endurance or perseverance,” I replied, pleased that she had noticed such a detail. “It will enable you to use your injured hand more easily today while it may still feel quite uncomfortable – not that you seem to need help with fortitude, Highness.” She looked puzzled. “The astringent,” I said by way of explanation. “You bore it without flinching.”

She looked at me fixedly a moment, then nodded for me to continue. I recited the Invocation to Hecate and let a drop of wax fall on each talisman before gathering them up into a small linen pouch. I replaced the candle in its holder and held the pouch above it, high enough that I could barely feel the flame’s warmth. I began an incantation. After a single iteration of the words, the candle flared upward, scorching the fabric of the pouch. I extinguished the candle and let a final drop of wax fall onto the scorch mark, completing the spell. I handed the newly made charm to the princess, and bowed.

“That was quick,” she said, tying the drawstring around her neck.

“I have a lot of practice at halmakings.”

“Mmmm,” she said, her tone conveying approval without any hint of an invitation to further talk. I gathered up my things, bowed again, and left.

The princess summoned me the following day, and I wondered if she was dissatisfied with my work. When I arrived in her quarters, she held up her hand: the bandage was removed, and the injury healed over with tender pink skin. It looked fine to me – exactly the way it should look the day after the spell.

“Does it still give you discomfort, Highness?” I asked.

“Not the slightest,” she said, and waited for a response.

“In that case, what can I do for you, Highness?”

“Mmmm,” she said.

“Highness? If you are happy with the spell, shall I go?”

To my surprise, she laughed sweetly. “Is my company so awful, Spellwright? Have a seat.” I obeyed, and she gave me the same fixed look as before. “You don’t seem surprised that my hand has healed.”

I dipped my head in acknowledgement. She raised an eyebrow and waited for a more substantial response. “I’m not surprised, Highness,” I said. “It was an uncomplicated injury, and the spell went smoothly. There was no reason it should be slow to heal.”

“It was a deep cut,” she said, sitting forward in her chair to lean toward me. “You said yesterday you have a lot of practice at halmakings. How many cuts deeper than that one have you healed?”

“Many.”

She leaned back again, looking slightly annoyed. “Can you be more specific, Spellwright? Please.”

I inhaled deeply, not relishing this turn in the conversation. “My father is a retired infantryman, Highness, and a respected citizen in our village. So when Aresia invaded the north, half the people I knew enlisted, to follow his example – to follow him… to glory.” The words stuck in my teeth. “Some of them came back…”

“Mmmm,” said the princess gravely, and I realized in a gush of relief that she needed no further explanation. “You must have been very young.”

“Eighteen, Highness.”

She looked at me steadily, and I felt her gaze like a calming benediction. She would have been a child of ten when the war started, yet I could see in her expression that she knew – the death, the loss, the bodies maimed and spirits broken. Finally she said “I cannot imagine you were using hummingbird eggshells then.”

My eyes fell to the floor, my mind flashing back to a scene I preferred not to revisit, bending over badly injured women and men, some no older than myself, with only a stump of tallow candle and a sliver of carefully rationed ginger leaf wrapped in a dirty rag. Doing what I could with the supplies Damia and I had. Watching the dying suffer, with no calming jasmine to give them. Bandaging wounds that would disfigure or cripple with only the mild magic of ginger to encourage regeneration. Saving my one remaining lotus petal for him, for Tully, my first betrothed, who never came back from Comana.

The princess called my mind back to her presence gently, with a hand on my shoulder. “I’m sorry,” she said, switching into the informal speech of an old friend. “I should not have asked.” Her small hand was as warm as a barley poultice, and as firm as the mortar on a cottage wall. She waited until the tension had drained from my posture, and then switched back to the formal mode. “However many you lost, I would entreat you to remember the lives you did save, Spellwright. Your country thanks and commends you for every one of them.”

She withdrew her hand, and I bowed my head to hide my tears. I ached to fall on my knees, under the weight of the sudden certainty that I would do anything for her – my princess – now and always.

Recalling that moment – lingering over every aching detail – did not help me sleep. Caught between the pleasure of the memory and the pain of its distance, I felt torn open, like a sapling bent by a storm at its top and held fast in the ground at its roots until the wood splintered. Half the night crept by in unhappy silence before I finally fell asleep, and sharp sorrow gave way to restless, fitful dreams.